Prescribing Antipsychotic Drugs to California Foster Children Has Declined Dramatically

A new study in California recently indicated statewide reforms have freed thousands of abused and neglected children from the lasting effects of the most powerful psychiatric drugs, but concerns about other medications persist.

What’s behind the dramatic decline?

California has dramatically curbed its use of antipsychotic medication to control emotionally troubled foster children, according to a new study – raising hopes of a changing culture in the years since a Bay Area News Group exposed the rampant use of those powerful drugs.

Researchers found a 58% drop in prescriptions of antipsychotics – the most powerful and concerning psychiatric drugs – for California’s abused and neglected children over the span of a decade – although the use of all drugs held steady.

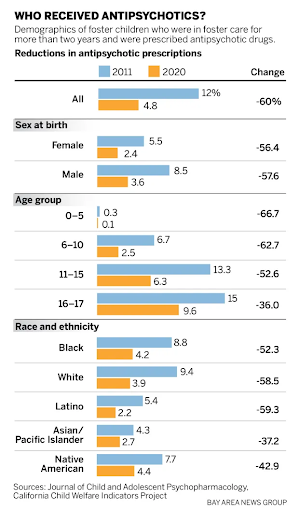

The sharp decline for antipsychotics between 2011 and 2020 held true across every foster care age group, children of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, and all regions of California.

Julio Nunes, a Yale University resident psychiatrist and lead author of the study, called the findings – and their impact – heartening: Reducing medication for children who don’t need it, he said, gives them more opportunities to thrive.

“If they are not numbed, they can pay more attention in school and with friends, and have more meaningful conversations about their trauma with trusted professionals,” Nunes said. “That all increases their potential for growth.”

In a 2014 series “Drugging Our Kids,” the Bay Area News Group highlighted the state foster care system’s reliance on psychiatric medications to blunt disruptive behavior and the impacts of trauma on children wrenched from their families.

Antipsychotics – designed to treat adults with severe mental illnesses – not only daze children into a stupor, these medications often saddle them with diabetes, obesity and irreversible tremors.

In 2011, 7% of the 78,231 California children in foster care – or 5,570 kids – were prescribed antipsychotics. But in 2020, just 3% of the state’s 68,386 foster children were given the medications, a total of 2,068 children.

The drop was especially pronounced for children younger than 10. What’s more, racial and ethnic disparities in prescribing have been nearly eliminated since 2011: Black, Latino, White, Asian and Pacific Island and Native American youth all saw declines between 38% and 59%.

Not all of the news was positive: Nearly half of the foster youth who continued receiving antipsychotic drugs were not properly monitored for the drugs’ side effects; The lack of testing for things like spikes in blood glucose and cholesterol levels represented a “concerning” lack of required medical oversight.

Still, child psychiatrists and former foster youth were encouraged by the overall trend.

The use of psychiatric medications of all types – including mood stabilizers, antidepressants and stimulants – appears to have mostly remained flat over the decade, at more than 12% of all foster children. That’s more than 2.6 times the rate of the general population, according to state data.

State officials were prompted to act after the Bay Area News Group investigation led to a slate of legislative reforms that improved how officials tracked medication use and doctors’ prescribing practices – along with new requirements for judges, social workers, public health nurses, pharmacists and clinicians.

State officials were prompted to act after the Bay Area News Group investigation led to a slate of legislative reforms that improved how officials tracked medication use and doctors’ prescribing practices – along with new requirements for judges, social workers, public health nurses, pharmacists and clinicians.

Bay Area News Group’s series revealed that nearly 1 out of every 4 adolescents in California’s foster care system – and 15% of all kids – received some type of psychiatric drug – often medication that was not approved for children.

It found that the state’s most prolific prescribers were responsible for about half of foster children receiving powerful antipsychotics, and that those high prescribers often had close ties to pharmaceutical companies manufacturing the drugs.

While the reforms could be putting a chill on over-prescribers, California’s medical board has yet to crack down on any doctors under scrutiny.

Post a comment